A sick or injured horse creates an immediate problem for a farm manager, but usually it is a problem with a relatively simple solution: Call the veterinarian! Less obvious, at least in the heat of the emergency, is the question of who pays for the veterinary services when the bill comes due weeks later.

- Will the vet bill go directly to the horse owner, or to the farm manager who writes a check, then bills the client for reimbursement?

- What if the client refuses to pay the veterinarian, or to reimburse the farm manager?

- Are there situations in which the farm manager will be financially obligated to the veterinarian with no hope of reimbursement from the horse owner?

The question of who ultimately pays the bill when a farm manager secures necessary services from a third party on behalf of a client is not limited to veterinary care. Other common third-party providers who expect to be paid for their services include farriers, van companies, and anyone else who does work at the request of a farm manager on behalf of a horse owner.

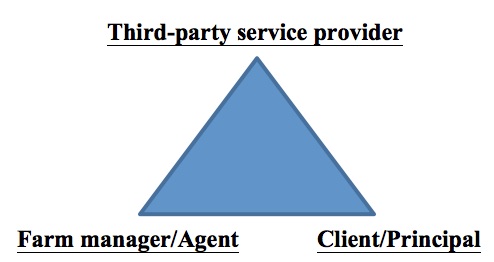

Working out the financial permutations requires a basic understanding of the “agency triangle.”

Agency is a legal relationship between two individuals—the “principal” and the “agent”— in which the principal authorizes the agent to conduct business on his behalf. This grant of authority allows the agent to negotiate with a third party for the benefit of the principal, and in the process create a financial or contractual obligation that the principal must satisfy. An agent has a fiduciary duty to the principal, which means that the agent must act in the best interest of the principal.

An agency relationship may be either “actual,” a formal arrangement in which the agent is employed by the principal, or “implied,” where the relationship between the parties can be established by their conduct toward each other and with third parties. Actual agency results from a contract or other formal agreement between a principal and the agent; implied agency arises when the parties act as if one party is the agent of the other. When a horse owner pays a bill for third-party services ordered by a farm manager, for example, a reasonable inference is that a principal-agency relationship exists. With either actual or implied agency, a third party can expect to be paid by the principal for goods or services requested by the agent.

In the horse business, agency relationships most often are associated with buying and selling, common situations in which a bloodstock agent represents either the buyer or the seller in a sales transaction. When a bloodstock agent negotiates the purchase of a horse, for example, the resulting deal is binding on the agent’s principal, who may be either the buyer or seller.

Occasionally a single bloodstock agent will represent both the buyer and the seller in a sales transaction. The practice is called “dual agency” and it comes with an inherent conflict of interest arising from the fiduciary duty an agent owes his principal. The best interest of the seller is to obtain the highest price for a horse, while the best interest of the buyer is to get the horse for the lowest price possible, and acting in the best interest of one party necessarily means acting against the best interest of the other. A few states, including Kentucky, Florida and California, have statutes prohibiting dual agency in horse sales unless both the buyer and the seller agree in writing.

The scope of the agency relationship is much broader than simply the sales context, however, and can include any situation in which one party acts on behalf of another person. Our hypothetical is an example in which determining whether the farm manager or the horse owner ultimately pays the veterinarian’s bill depends on whether a principal-agent relationship exists. If the farm manager was acting within his authority as agent, the horse owner is financially responsible for the bill. If there was no agency relationship, on the other hand, the bill goes to the farm manager.

A Case On Point

A lawsuit brought in the City Court of Rye, in Westchester County, New York, illustrates the importance of an agency relationship between farm manager and client.

Standardbred trainer Dennis Laterza conditioned horses at Yonkers Raceway in New York for a number of clients, including Calvin Oliver International Racing, Inc. When two of the Calvin Oliver horses became ill, Laterza put in a call to Dr. Vincent DiCicco, his regular veterinarian. Dr. DiCicco treated the two horses over a period of three months, in the process sending monthly invoices for his services to Calvin Oliver International Racing. The first bill, for $645, was paid without complaint, but the horses’ owner refused to pay the subsequent two bills totaling $1,920. Dr. DiCicco eventually sued in small claims court to collect the delinquent bills. The small claims court judge ruled in Dr. DiCicco’s favor and awarded him the full amount due.

At trial and on appeal, the horse owner admitted that he owned the horses in question and that Dennis Laterza was his trainer during the period when Dr. DiCicco treated the hoses. A question of agency arose when the horses’ owner argued that he had no obligation to pay Dr. DiCicco’s invoices because Laterza had no authority to call the veterinarian on the owner’s behalf. Instead, the horse owner claimed that he had given specific instructions to Laterza that only a particular veterinarian practicing in Port Deposit, Maryland, was authorized to treat the horses. Port Deposit is located approximately 170 miles from Yonkers Raceway, where Dr. DiCicco treated the Calvin Oliver horses.

The appellate court did not specifically addressed the impracticability of a veterinarian in Port Deposit making a 340-mile round trip to Yonkers numerous times over a three-month period as a rationale for awarding the disputed fees to Dr. DiCicco. The trial judge simply ruled, and the appellate court affirmed, that Laterza “had actual or apparent authority to engage [Dr. DiCicco]’s services” and that the trial court’s judgment rendered “substantial justice between the parties.” In other words, the trainer was the owner’s agent and in that capacity could incur expenses such as vet bills on the owner’s behalf. The horse owner’s request to re-argue the case before the appellate court was denied.

A strong legal argument supporting the court’s decision in favor of the veterinarian was the fact that Dr. DiCicco’s first bill to Calvin Oliver International Racing, Inc., was paid, apparently without complaint. Whether there was an actual agency agreement is not clear from the brief appellate decision. Even if there was not actual agency, however, payment Dr. DiCicco’s first invoice arguably ratified trainer Laterza’s authority to act as Calvin Oliver’s agent in securing veterinary services for the owner’s horses.

If the court had determined that there was no agency agreement between Laterza and his client, on the other hand,Calvin Oliver International Racing, Inc., would have had no obligation to pay Dr. DiCicco’s bills. In that case, financial responsibility for the veterinary care would have fallen to the trainer.

The take home message reflects good business practices for a stable owner or manager:

- Always utilize written contracts that acknowledge the existence of an agency relationship between the farm owner/manager and the horse owner;

- Establish the parameters of the agency relationship in the contract to avoid misunderstandings, including the authority of the farm owner/manager to call a veterinarian in an emergency, or if reasonable efforts to contact the horse owner or a specified veterinarian are unsuccessful;

- Inform third-party service providers of the agency relationship before the services are needed, and request that the horse owner be billed directly.