Researchers from the University of Kentucky Veterinary Diagnostic Center reviewed the number of cases of Potomac horse fever that came into the laboratory for necropsy, comparing those diagnosed before death and those diagnosed at necropsy based on PCR findings. Contributing to this research was Craig Carter, DVM, PhD; Jacqueline Smith, PhD; and Erdal Erol, DVM, MSc, PhD.

Equine monocytic ehrlichiosis (EME) is also known as Potomac horse fever (PHF) and equine ehrlichial colitis. The disease has since been reported in most states in the U.S., at least three Canadian provinces, and also in parts of South America, Europe and India. The disease usually occurs near rivers, lakes and wet pastures from mid- to late summer.

The cause of EME is Neorickettsia risticii, formerly Ehrlichia risticii. The reservoir for the causal agent is not clear but it has been isolated from ticks, aquatic insects, flukes and other helminths. Snails act as an intermediate host in the fluke cycle. Horses are thought to be infected through the ingestion of insects, often mayflies, which may land in drinking water. Experimentally, the incubation period ranged from 1-3 weeks in horses.

In the early stage of the infection, horses may become anorexic, depressed, pyrexic and have decreased gut sounds. This is usually followed by loose stools or watery diarrhea and colic. In the late stages of the disease, affected animals may have severe dehydration, ventral abdominal edema, and laminitis. Death is the consequence of cardiovascular compromise and toxemia. Case fatality rates range from 5-30%. Transplacental transmission is reported often leading to fetal resorption, abortion, or weak foals. Horse-to-horse transmission is not thought to occur.

Horses that recover from the disease may have protective immunity for up to two years. Available vaccines appear to have variable efficacy. Limiting proximity of horses to rivers, ponds, lakes and low-lying pastures during the peak EME season and eliminating lighting at night in horse stables to minimize attraction of insects may reduce the risk of infection.

A provisional clinical diagnosis of EME needs to be confirmed by a veterinary laboratory competent in diagnosing the disease. A single positive indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test result for EME on serum only indicates exposure to the agent. Paired blood samples collected two weeks apart demonstrating a four-fold or greater rise in titer is evidence of an active infection. In clinical cases, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay should be performed on an EDTA blood sample as well as on a fecal sample, as presence of the causal organism in blood and feces may not temporally coincide. At necropsy, a scraping of the colonic mucosa is the specimen of choice for PCR testing for EME.

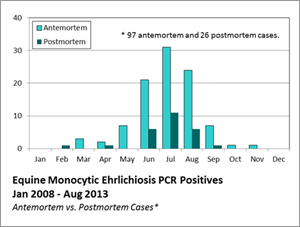

From January 2008 through August 2013, the University of Kentucky Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory had 123 equine samples submitted that tested positive for EME by PCR. Included in this number were 26 horses submitted for necropsy that were diagnosed with EME. Of the necropsy cases, the sex distribution was 53% female and 47% male. The mean age distribution was 8.7 years (range 0.3-34 years). The breeds involved were mostly Thoroughbred.